Born in 1780 in the town of Montauban, France, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres was the son of Jean-Joseph who was himself a sculptor, architect, musician and painter. The pair enjoyed drawing, singing and playing the violin. At the tender age of eight, the boy performed in public and by nine he was already creating drawings of merit and was attracting some notice.

Born in 1780 in the town of Montauban, France, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres was the son of Jean-Joseph who was himself a sculptor, architect, musician and painter. The pair enjoyed drawing, singing and playing the violin. At the tender age of eight, the boy performed in public and by nine he was already creating drawings of merit and was attracting some notice.

The father had hoped the son would have a successful career in music. By the time Jean Domininque was eleven; his path was firmly rooted in the arts, not just in the direction his father had hoped for. By then, he was attending the Academy of Fine Arts in Toulouse studying painting and sculpture. Young Ingres supported his studies as a musician in the Orchestre du Capitole de Toulouse, as the second chair violinist. Ingres would find peace and solace in playing the violin and would turn to it throughout his life. In some ways, his father’s wish for his son to become known for his musical abilities did indeed come to pass. He was so well-known for his love of the violin that the French phrase “violon d’Ingres” would come to be used to refer to any cherished and sustaining hobby.

While studying at the Academy, Ingres also attended outside classes and studied drawing with pen, ink and crayon. He spent much of his free time copying the works of the great masters.

While still a teen, young Ingres began to win prizes for his work. When he left for Paris in 1797, one of his teachers said that Ingres would become a distinguished artist who would bring honor to France. Upon his arrival in Paris, Ingres began studying with Jacques-Louis David, a well-known artist of the French academic school and France’s leading painter during the revolutionary period.

As a student at the Ėcole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Ingres continued to impress and was honored with numerous awards and prizes. He supplemented his studies by also attending the Swiss Academy, a somewhat informal art school which would later become a gathering place for more rebellious artists. At the Academy, students painted from living models rather than lifeless Greek and Roman sculptures. He further honed his craft making charming pencil sketches of anyone willing to sit for him. His sketches, which were often flattering of his subjects, would become quite popular and provide Ingres with a somewhat reliable source of income.

In 1800, he tied for second place in the Grand Prix de Rome and won the coveted award in 1801 with his work the Ambassadors of Agamemnon in the tent of Achilles (another scholarly work referred to the painting as “The Envoys of Agamemnon, Sent to Achilles to Urge Him to Fight, Find Him in His Tent with Patroclus Singing of the Feats of Heroes.”)

It would be five years before the cash-strapped government would present Ingres with his prize – a stipend to study in Italy. While waiting, he supported himself by continuing to paint portraits and selling an occasional sketch to a publisher. During this time, France provided the artist with shared studio space and awarded him several commissioned pieces.

By the age of 23, Ingres had already begun to make a name for himself in the art world. It was then that Napoleon himself sat for Ingres for a portrait to be given to the city of Liége. Ingres considered drawing the base of all paintings. He considered color useful for “filling in” the spaces created by drawn lines. His sitters would often provide him with samples of their garments so that Ingres could add the color at a later time.

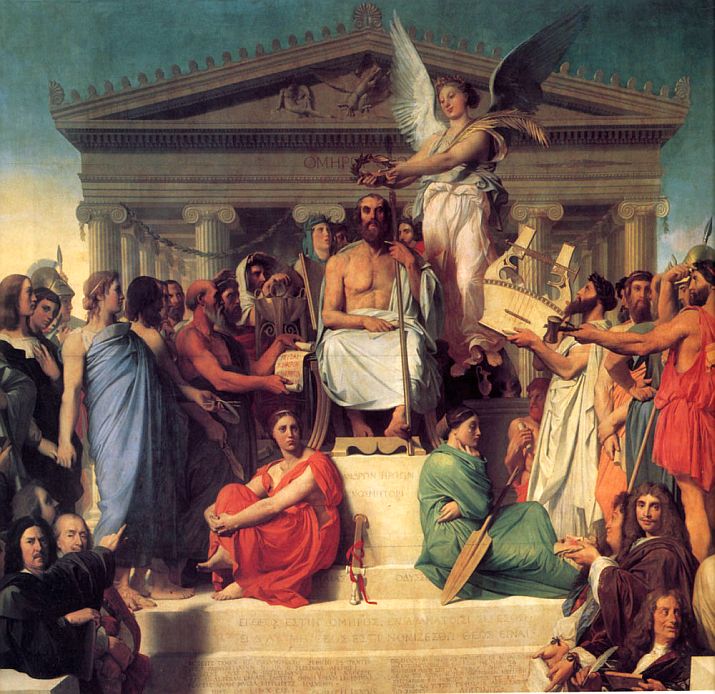

Ingres left Paris prior to the opening of the Salon of 1806. That year, his portrait entitled Madame Riviére and others were heavily criticized as being “bizarre and Gothic!” Ingres had gone outside the accepted conventions of classicism by painting with Madame Riviére by depicting draping folds of fabric and disproportionately sized arms in a masterpiece his fellow artists deemed against academic convention. When Ingres finally arrived in Italy, it was the artist Raphael who left him awestruck. He had seen examples of Raphael’s work at the Louvre, but it was the murals Disputa, Pernassus, and the School of Athens that he saw at the Vatican which would later influence much of his work.

Disillusioned and confused, Ingres traveled to Rome, where he would remain in a sort of self-imposed exile for 14 years. After two failed engagements, friends introduced Ingres to Madeline Chapelle claiming it was time the artist should have a wife. Madeline was the cousin of one of his friends. He proposed to the young woman he had never met via letter, they met at the Tomb of Nero and were married in 1813. They lived happily together until her death. He continued to send pictures to the Paris Salon exhibitions, as was required from a Prix de Rome winner, but they earned little. At one time, his wife lamented that they had no more bread and had no more credit with the baker.

Ingres continued to paint in his own unique style, not quite classicism and not quite romanticism. The artist himself never recognized the romantic influence in his works. The couple lived in Florence from 1820 to 1824, where he spent four years on a single commission for the cathedral in Mountauban.

In 1824, Ingres submitted his commission, a large religious picture entitled The Vow of Louis XIII, to the Salon. Despite relying greatly upon the works of Raphael, the work received great acclaim. The establishment forgave his earlier transgressions into the Gothic style deciding such an imitation of a certified old master earned the renegade artist redemption. The classical school had found a new champion in Ingres and he quickly became the movement’s chosen leader. The acclaim put him at even further odds with a young artist Ingres considered an upstart – Delacroix. The two would come to be seen as rivals within the classical school and each had his own followers. Delacroix recognized Ingres’s talent and contributions but Ingres only recognized Delacroix’s talents after the younger artist’s death.

In 1825, Ingres was elected a member of the Academy of Fine Arts. This honor brought the struggling artist important and lucrative commissions. He returned to Paris and opened a private art school and also taught at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. He would become the director of the Ecole in 1829. While no longer hungry, Ingres found himself still fending off rivals and conflicts over his art. He was known as demanding, prone to fits of temper and possessing a caustic tongue. People feared him. Ingres, in his new role, would instruct as many as a hundred students at a time. Delacroix remarked of his rival that he was teaching beauty as one teaches arithmetic.

He continued to paint in his own style and when his The Martyrdom of St. Symphorien was poorly received in 1834, Ingres asked to be transferred and serve as the Director of the Academy in Rome. Once in Rome, he refused all commissions and forbid any of his works from being shown in the Salons. He continued to paint but returned to his earlier themes based on Roman mythology which had been met with such disdain by his contemporaries.

In 1841, Ingres returned to Paris and received many awards for two of his works completed while in Rome.

When his beloved Madeline died in 1849, Ingres was inconsolable and unable to work. He traveled after her death until the fall of 1850.

In 1852, Ingres, at the age of 72, once again found himself in love; this time with a women 30 years younger than himself. The artist married Delphine Ramel shortly after they met.

After much convincing, he relented on his vow to never again allow his paintings shown in the Salons. Seventy of his pictures were hung as part of “Salle Ingres” in the Universal Exposition of 1855. Delacroix was similarly honored with a room dedicated to his works. Ingres painted La Source in 1856 and it would become one of his most beloved and famous paintings despite being deemed by some not equal to his earlier works. He was happy in his work and in 1862 was named a Senator of the Empire by Napoleon III.

Shortly before his death, Ingres was seen copying a painting by the 14th century painter Giotto. When asked why the master artist was doing so, he responded, “To learn!”

Dominique Ingres died on January 14, 1867 at the age of 87. Ingres is most well known for his portraits and historical paintings. Many of his historical works are influenced by Roman mythology and are often composed of sexual themes. To keep The Famous Artists a family friendly website, we will only be showcasing those works which may have sexual themes but do not display unclothed subjects.

Born in 1780 in the town of Montauban, France, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres was the son of Jean-Joseph who was himself a sculptor, architect, musician and painter. The pair enjoyed drawing, singing and playing the violin. At the tender age of eight, the boy performed in public and by nine he was already creating drawings of merit and was attracting some notice.

Born in 1780 in the town of Montauban, France, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres was the son of Jean-Joseph who was himself a sculptor, architect, musician and painter. The pair enjoyed drawing, singing and playing the violin. At the tender age of eight, the boy performed in public and by nine he was already creating drawings of merit and was attracting some notice.