The French Impressionist painter Edouard Manet has become almost as famous for the “Salon des Refusés” as for his canvases. Some say both changed the world of art in 1863. But, things may have turned out differently if Edouard’s father hadn’t allowed the budding artist to follow his dreams.

The French Impressionist painter Edouard Manet has become almost as famous for the “Salon des Refusés” as for his canvases. Some say both changed the world of art in 1863. But, things may have turned out differently if Edouard’s father hadn’t allowed the budding artist to follow his dreams.

Edouard was born in Paris in January of 1832 into a wealthy family. His mother, Eugénie-Desirée Fournier, was the daughter of a diplomat and goddaughter of the Swedish crown prince and his father Auguste was a French judge. By the age of ten, as a new student at Rollin College, he proved to be a poor student. Inattentive and reluctant to study, Edouard would rather use his notebooks for sketching than taking class notes. Sundays were a favorite for young Edouard for it was on Sundays that his uncle, Charles Fournier, would take him and his friend Antonin Proust to the Louvre. Edouard would remain life-long friends with Antonin who would become Minister of Fine Arts. Unfortunately, for their scholarly pursuits, those days spent viewing masterpieces only drove both boys to further abandon their studies in favor of drawing what they had been inspired by the Sunday before.

Growing frustrated with his son’s preoccupation with making pictures, Auguste, told Edouard to either “study the law” or make a career for himself in the Navy. Edouard chose the Navy, but failed the entrance exams. Determined to follow his father’s wishes, 16-year-old Edouard, sailed on the Havre de Guadeloupe to Rio in 1848. Instead of learning a love of sailing, he developed a love for the sea and the glorious colors of a sunshine soaked tropical landscape. His father reluctantly agreed to allow Edouard to pursue a career in art and allowed him to become a student of Thomas Couture. Along with his friend Antonin, the two studied the academic and technical painting traditions which dated back to the 17th century.

Manet remained with Couture for six long years. Manet never really liked his teacher who has been described as “pompous, eggocentric and an extreme opportunist.” It was said he learned much from Couture in using a brush but it was already clear, Manet’s style would differ greatly from that of his teacher. It was during his time at Couture’s studio that Manet met a Dutch piano teacher named Suzanne Leenhoff with whom he had a son in 1852. While in the art community such goings on may have been acceptable, it was far from acceptable among Manet’s parent’s set. Rather than risk losing his allowance, the pair told Manet’s parents that the child was Suzanne’s younger brother. That allowance allowed the artist to travel to Holland, Germany and Italy to study the work of the famous artists who lived there. The two married in 1862, shortly after his father Auguste died.

Around 1855, Manet entered the Swiss Academy. The Academy offered no formal instruction. What it did offer was access to nude models to sketch or paint. The artists shared expenses and learned from each other. Like so many of his fellow students, Manet also spent a great deal of time in the Louvre studying and copying the works or the Italian primitives and the Renaissance masterpieces housed there.

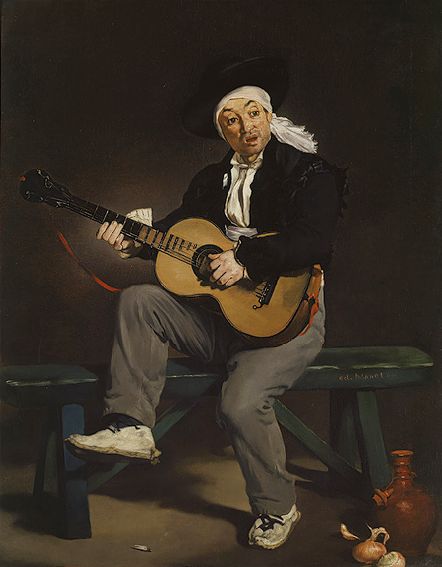

Manet rented studio on the rue Lavoisier in 1856. It became a gathering spot for the younger artists who were leading a rebellion of sorts against the academic painting traditions. Manet’s Spanish Singer was submitted to the Salon and did receive some accolades in1861. However, the rebels were generally labeled as “madmen” within the art world and the stage was soon set for the infamous “Salon des Refusés.”

Preferring more academic pictures, that jury choosing the pictures for the 1863 Salon excluded a significant number of paintings. The jury, showing more than a little favoritism was accused of trading votes as they rejected over 4,000 paintings. Some paintings from young and inexperienced artists were rightly excluded but a large number were equal in workmanship to those works which had been accepted. The artists raised such a fracas, that Napoleon III wanted to see what was causing so much discontent. He and the Empress reviewed several of the excluded paintings and found them to as good as what had been selected and wanted the public to decide the legitimacy of the complaints. Despite the protests of the jury, Napoleon ordered a second exhibit be placed adjoining the first called the Salon des Refusés. Painters were given the option to withdraw their works – a similar show of rejected works a few years earlier was poorly received. 600 paintings were withdrawn.

Unfortunately for the Emporer, included among the excluded paintings which he did not review, was one by Manet which would shock the art world to its core. The painting was titled simply enough – The Bath. It would later be renamed to Luncheon on the Green. It takes inspiration from Marcantonio Raimondi’s 1515 engraving of the Judgement of Paris which is itself based on a drawing by Raphael. Not identified as a Venus or other figure out of mythology, Manet’s nude simply became a naked girl scandalously in the company of several completely dressed men in the open countryside along with a half-eaten meal. Bohemian is what many called it. The art world found fault with his sketch-like handling of the subject. Napoleon called it immodest. Others found it downright offensive.

It became the must see piece of the exhibition. Unfortunately for Manet, who was a cultivated gentleman who would have preferred conventional success, he gained success through scandal – the absolute last thing he wanted to see happen.

The Salon des Refusés began a monumental shift of power within the art world. Rather than be constrained by what the Salon juries considered acceptable, artists were slowly being given the right to paint as they pleased. The Salon system punished those who innovated and in effect practiced a form of censorship based upon esthetics, often relating to the technique and style of the paintings. The Salon des Refusés played a major role in ending that practice.

But, as for shock value, it was Manet’s Olympia that really set the tongues wagging. It has strong similarities to Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538) and Goya’s The Nude Maja (1800). The model was Victorine Meurend. In the painting, she is naked and reclining on a bed, wearing only slippers and jewelry. A fully dressed servant is presenting her mistress with a box of flowers. A black cat sits proudly at the end of the bed. At that time, many of the items included in the painting were symbols of sexuality. Again, this was not a painting of a goddess but of a mere woman, probably a courtesan awaiting the arrival of her lover. The work was actually physically attacked and Manet left the country in fear of his safety. The Famous Artists won’t be sharing this painting due to its decidedly not-family friendly nature, but does mention it here due to its pivotal role in Manet’s career.

By 1865, Manet’s place in history was fairly assured. His technique of using a bright undercoating to reflect light went contrary to the traditional method of first completing a piece and then applying layers of glaze to achieve the illusion of form. Though labeled as being an Impressionist, a derogatory term at the time, he was perhaps the best known of his group of fellow artists which regularly met at the Café Guerbois in Montmartre, Avenue de Clichy. His work continued to show a strong Spanish influence deeply rooted from his days as a young man copying the great works housed in the Louvre.

In 1867, at his own expense, Manet built his own exhibit hall to show his works rather than participate in the Great Exhibition being held that year. (Our research had contradictory information – some said he opted out of the exhibition others said he had been refused admission.) His art was becoming more accepted but critics remained.

Le Bon Bock (The Good Mug of Beer), painted in 1873 was a huge success. It was a painting that the press and the public understood and enjoyed.

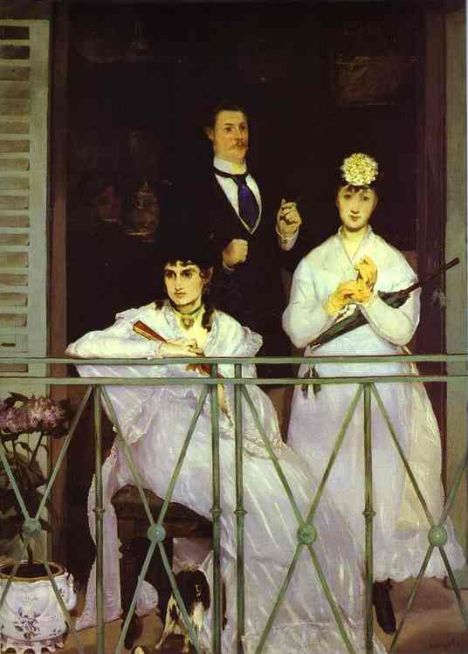

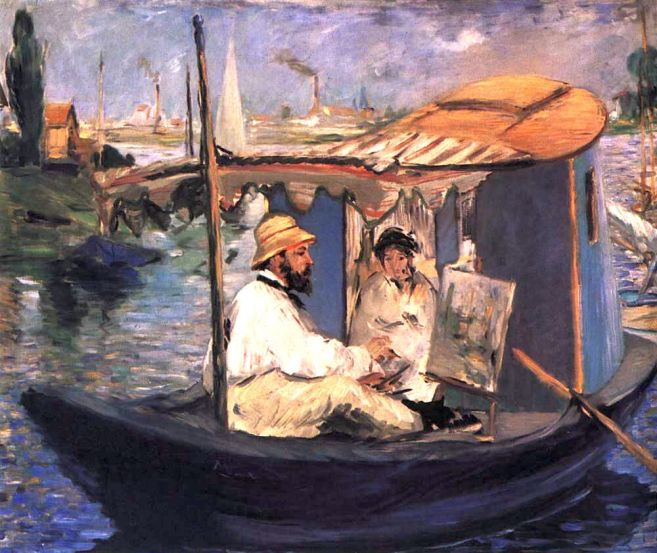

Despite this success, Manet turned to a new style. He met Claude Monet, Renoir, Alfred Sisley and Camille Pissarro. Those artists and others he met at the cafe, including Berthe Morisot whom he met in 1868, further introduced Manet to the Impressionist style and the concept of painting in “plein air” and different uses of color. Morisot would marry Manet’s brother Eugene in 1874.

By 1877, the group had chosen the Café de la Nouvelle Athenés as their preferred nightly meeting place. Manet could be found sitting with other famous artists such as the painter and sculptor Degas and the Irish Novelist George Moore. A sketch by Manet of Moore can be found….

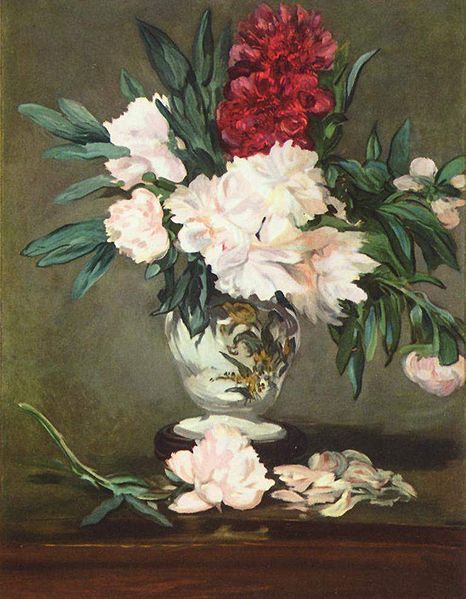

Manet’s health began to deteriorate. He retired to Bellevue but continued to paint flowers, still lifes and portraits (often of beautiful women wishing to pose for the famous artist). His childhood friend, Antonin Proust was the Minister of Fine Arts and played a major role in awarding Manet the Star of Chevalier of the Legion of Honor in 1882. In terrible pain and unable to paint, Manet turned to pastel crayons. His left foot was amputated in hopes of saving him but he succombed to his illness in 1883.

The poet Moore wrote of his friend Manet in his Confessions of a Young Man:

What he has got, and what you can’t take away from him, is a magnificent execution. A piece of still life by Manet is the most wonderful thing in the world; vividness of colour, breadth, simplicity, and directness of touch–marvellous!

The French Impressionist painter Edouard Manet has become almost as famous for the “Salon des Refusés” as for his canvases. Some say both changed the world of art in 1863. But, things may have turned out differently if Edouard’s father hadn’t allowed the budding artist to follow his dreams.

The French Impressionist painter Edouard Manet has become almost as famous for the “Salon des Refusés” as for his canvases. Some say both changed the world of art in 1863. But, things may have turned out differently if Edouard’s father hadn’t allowed the budding artist to follow his dreams.