Sewing Women

A quiet painting of two sewing women by the French artist Jean-Francois Millet.

My goal with the biographies of famous artists is to hopefully dig below their art and focus on who they were and leave the scholarly artistic conversation to others. When I can, I prefer to work from personal letters and the information provided by contemporaries and friends of the artist over more scholarly works. In the case of Jean-Francois Millet, we are fortunate that Alfred Sensier saved his correspondence with the artist and gathered letters written to others by Millet. Some of the information contradicts what appears in more scholarly works but when it comes to something like how many children someone has – I tend to think that friends and family are more accurate than an online encyclopedia.

My goal with the biographies of famous artists is to hopefully dig below their art and focus on who they were and leave the scholarly artistic conversation to others. When I can, I prefer to work from personal letters and the information provided by contemporaries and friends of the artist over more scholarly works. In the case of Jean-Francois Millet, we are fortunate that Alfred Sensier saved his correspondence with the artist and gathered letters written to others by Millet. Some of the information contradicts what appears in more scholarly works but when it comes to something like how many children someone has – I tend to think that friends and family are more accurate than an online encyclopedia.

Sensier utilized personal memories and over 500 letters to write what would become a work that many consider the main biography of Millet. Sadly, Sensier did not live to complete the project but his friends and family ensured that his book would be finished and published.

I have primarily followed that biography but have also included information from a number of other sources.

He was born in 1814 in the village of Gruchy in the Normandy region of France and named for his grandmother’s favorite saint – St. Francis of Assisi. Assisi, an observer of nature would be an apt role model for the French painter. They were peasant farmers, living and working together like most of the other families in their village. His parents worked the land, while his paternal grandmother and her brother Abbe Charles tended to the children. It was a large family with eight children. As the eldest boy, it was most likely assumed, from the time of his birth, that he would one day take over the operation of the family farm and raise his own children there. It was those humble beginnings and his love of the land that led him to become one of the most influential painters of all time.

His first teacher was his grand-uncle. Before reaching his teens, he was reading classical literature in both Latin and his native French. The local vicar would become his second teacher upon the death of Abbe Charles. Young Jean-Francois went to Heauville, when the vicar was transferred there but became too homesick to remain with his new teacher.

Jean-Francois’s artistic abilities were already starting to emerge. His father, not without some artistic abilities of his own, made rough sketches, simple clay figures and wood carvings for his son to copy and draw. Pictures from the family Bible provided inspiration and lessons on technique. And, the natural beauty of the French countryside would feature prominently in his early works.

Wondering if Jean-Francois possessed the talent to become an artist, Millet took his son and some of his work tot a local painter named Mouchel. Mouchel at first did not believe the pair that such a young artist could paint with such maturity and skill. He accepted the young man as a student. However, fate intervened and after a few months, Jean-Francois had to return home when his father become ill.

Millet would die shortly thereafter and Jean-Francois assumed the role of managing the family farm.

The grandmother who raised him convinced Jean-Francois Millet to return to Cherbourg and continue his studies. Lucien-Théophile Langlois (1803-1845), the new tutor, instructed young Millet in much the same way his father and Mouchel had done – by simply encouraging the boy to paint without instruction. Millet spent his free time reading the works of Sir Walter Scoot, Byron, Goethe and Victor Hugo.

Langlois and his grandmother would petition the municipal council of Cherbourg to provide Millet an annuity to provide him with the funds to study art in Paris. With 600 francs in his pocket, warnings from his grandmother of the temptations of the city and misgivings about leaving two widows to run the family farm; Millet was off to Paris.

He found Paris quite overwhelming. He was laughed at for his unsophisticated country manner and would be swindled out of most of his money. Rather than risk further ridicule, Millet wandered the Paris streets in search of the Louvre. After days of searching, he was finally able to stand among the works of Mantegna, Michelangelo and Rubens.

In a letter to Alfred Sensier, Millet reminisced about his first trip to Paris and his views of art:

“I never studied systematically…I came to Paris with all my ideas of art fixed, and I have never found it necessary to change them. I have been more or less in love with this master, or that method in art, but I have not modified any fundamental opinions. You have seen my first drawing, made at home without a master, without a model, without a guide. I have never done anything different since. You have never seen me paint except in a low tone; demi-teinte is necessary to me in order to sharpen my eyes and clear my thoughts, – it has been my best teacher.”

He talked of a number of artists and was often blunt in his assessments. He called Francois Boucher’s women “little undressed creatures,” with feet deformed by high-heeled slippers, bloodless breasts and an overall appearance that was repulsive. He likened Antoine Watteau’s work to marionettes to be shut up in a box. He was, however, greatly impacted by Eustache Le Sueur (1617-1655) – “one of the great souls of the French school.” He called Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665) “the prophet, the sage and the philosopher, while also the most eloquent teller of a story. I could pass my life face to face with the work of Poussin, and never be tired.”

Millet was admitted to the studio of Paul Delaroche (1797-1856). Still seeing himself as the unsophisticated peasant farmer, Millet did not socialize with most of his fellow students. Sensier described Millet as being built like Hercules. He was 6 feet tall at a time when most men were a more petite 5 foot 5 inches tall. When pushed, he would speak with his fists, just as he did as a child of six on his first day of school when he pummeled the school-yard bully.

The other students and Delaroche did not understand Millet or his work and perhaps even came to fear him. Yet, they all seemed to recognize his talent; despite it being contrary to what was being favored at the time. Amidst a growing sense of his tutor’s inability to teach and the animosity of fellow students, Millet left Delaroche’s studio. He would return only after being consoled and invited back by Delaroche.

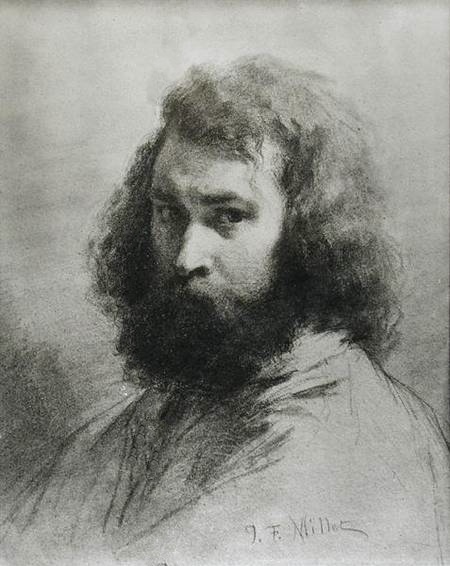

The irony is that Millet more than likely was more well-educated than the other students, who saw him as something of a “wild man of the woods”. (The self-portrait which accompanies this biography is from 1845 or 1846 and perhaps shows some of his size and wildness.) He could join their philosophical conversations and quote the classical literature he loved so much, yet he was not accepted by the artist or his other students.

The breaking point for Millet came when he set his eyes on winning the coveted “Prix de Rome”. It was a scholarship of sorts that would support the winner while they pursued historical landscape painting at the Villa Medici in Rome. Delaroche had already promised to support another student for the prize and told Millet that he would have to wait until the next competition – four years later. Millet left the studio for good. Fellow student and friend Marolle left with him. (I’ve found a number of mentions of Marolle without a first name or any other information. One source mentioned that Marolle’s father had done well in business and Marolle did not need to sell his paintings to survive.)

Millet remained in Paris and tried to sell his work. Unfortunately, no one was interested in dark landscapes with common laborers in the foreground. Popular belief was that landscapes were meant to be done in lighter colors and not include people. Marolle suggested that instead of paintings of people making hay, Millet should imitate the works of Watteau and Boucher. Marolle, a native Parisian, tried to help Millet sell his work but only a few of these works sold for small sums.

Millet submitted two works into the 1840 Salon. They chose the work that Millet described as “the poorer of the two; the color was somber and looked like the follies of the Delaroche studio.” They declined the portrait of Marolle, probably embarrassing both Millet and his biggest supporter.

Millet had been visiting his family annually. In 1840, he returned home permanently and hoped to make his living as an artist in Cherbourg. The town commissioned Millet to paint the portrait of M. Javain, their former mayor. Millet had never met the mayor before his death and the only available likeness was a poorly painted miniature of Javain as a young man. Millet made a huge mistake. To paint Javain’s hands, he used a convicted criminal for a hand model. He angered many of the influential members of the community and they refused to pay the promised 300 franc commission.

The lost commission could have proven disastrous but fortunately, he received some commissions for portraits by younger members of the community and for advertising signs.

In November of 1841, Millet married Pauline-Virginie Ono, a Cherbourg dressmaker. He despised her family and the marriage was not a happy one. The couple moved to Paris in 1842 and the Salon rejected both of his submissions that year. He submitted nothing in 1843. Pauline-Virginie was often ill during their marriage and died in 1844 after a prolonged illness.

Oddly enough, it was during this difficult time that Millet finally began to truly find his own style. He was still in mourning and often had trouble paying his debts and, yet, his work developed a warmth and charm. His figures were no longer black with thick shadows and he completely stopped following the traditions of the Delaroche studio. He painted with “the joy of a man who feels full of life and gifts, and who understands the secrets of the masters.” Diaz would say of Millet’s 1844 contributions to the Salon exhibition; “At last, here is a new man who has the knowledge which I should like to have, and movement, colour and expression too – here is a painter.”

He once again returned to Cherbourg around 1844. This time, he would be more successful. The town prefect offered Millet the post of Professor of Drawing at the Municipal College. Millet declined; he was determined to remain independent and hoped to return to Paris.

He met the love of his live, Catherine Lemaire; a peasant girl 12 years his junior. It is likely that without Catherine in his life, Millet would have sunk into obscurity and probably returned to farm life. She supported Millet in his painting even when that meant skipping meals to ensure their children had something to eat. They would have nine children and remain together for the remainder of Millet’s life.

In 1845, they stopped at Havre on the way to Paris. He did a number of portraits in Havre and became quite popular. A public exhibition was held. But, once the couple had accumulated 900 francs, they left for Paris.

Despite being surrounded by artists of all kinds, including the sculptor Armand Toussaint (1806-1862), animal painter and etcher Charles Jacque (1813-1894) and Narcisse Virgilio Diaz (1807-1876); Millet would feel trapped and imprisoned in Paris. Money continued to be elusive, a son was born and the Salon once again refused Millet’s submission. Millet was friends with a number of the more influential artists and they often urged dealers to get his paintings – that led to a handful of sales. In 1846, he often painted with pastels – lovely paintings of naked, innocent women and children. For a while, the other artists called him “a master of the nude.”

Alfred Sensier first met Millet in 1847 and they would remain close friends the remainder of Millet’s life. Sensier thought Millet had an “outlandish look.” When he first met the artist, he saw “A brown-stone-colored overcoat, a thick beard, and long hair covered with a woolen cap like those worn by coachmen, [which] gave his face a character which made on think of the painters of the Middle Ages.”

In the spring of 1847, Millet almost died from rheumatic fever. During his illness, it was only through the generosity of friends that the Millet family had food on their table and wood in their stove. He submitted two works to the Salon of 1848. The jury had been abolished and everything submitted was hung. One painting “left the public cold” but, “Winnower” was purchased by the Government for 500 francs. He also received a commission for 1200 francs from M. Ledru Rollin. Rollin was fairly well-known in France and would later sow the first seeds of the revolution by preventing the appointment of the duchess of Orleans as regent in 1848.

The revolution, perhaps, changed everything for the Millet family. He would be compelled to defend the Assembly and climbed the barricades in the Rochechouart quarter. He was there when the chief of the insurgents fell. Though he was greatly troubled by the slaughters and bloodshed, he felt no sympathy for the cause. He longed to leave Paris. People were only buying necessities during the uncertain times of the revolution and the Millet family was in trouble. They had gone two days without food to ensure their children could eat when they were given 100 francs by their friends.

He continued painting but sold very little. He began working on smaller pieces, encouraged by friends to try selling his work in exchange for practical items – he was able to trade paintings for clothing, shoes and even a bed.

It was a chance encounter that truly changed everything. Millet happened to overhear two young men discussing his “Women Bathing.” When one asked the other who the artist was, the reply was, “a fellow named Millet, who paints only naked women.” His dignity destroyed, Millet returned home and consulted with his wife about painting “no more of that sort of pictures.” He warned her that their financial situation would more than likely become even more bleak. Oddly enough, she agreed and he began painting what was then referred to as “rustic art.”

Cholera came to France. The family, seeking to find a cheaper place to live and escape the perils of living in the middle of the uprising, moved to Barbizon in 1849. Barbizon was a quiet town on the edge of the forest of Fontainebleau that welcomed artists.

Millet, not having enough money to pay for transportation from Fontainebleau, entered Barbizon on foot carrying his two little girls. His wife, also on foot, carried their son. Theodore Rousseau (1812-1867), Hughes Martin, Leon Auguste Adolphe Belly (1827-1877), Louis Leroy (a painter who would later become the critic who coined the term impressionism and like that painting style to incomplete wallpaper) and Charles-Ernest Clerget were already there. Diaz would welcome his friend to the community. Millet and Rousseau would begin a great friendship as well.

The Millet’s moved into a little house with three rooms – studio, kitchen and bed-room. Two additional rooms were later added as the couple would have six more children. Life developed into a routine of sorts. In the mornings, Millet tended his garden and after lunch, he painted.

Millet finally began finding his place in the world of art – depicting rural life as it was all the while showing the inner strength of his subjects. After a time, he began suffering from violent headaches. He took to the fields and forests and the open air seemed to restore him. Sensier remembers Millet exuding a child-like joy when climbing rocks, jumping and bounding around the forest of Fontainebleau.

In a letter to Sensier, Millet wrote,

“If you could see how beautiful the forest is! I rush there at the end of the day, after my work, and I come back every time crushed. It is so calm, such a terrible grandeur, that I find myself really frightened. I don’t know what those fellows, the trees, are saying to each other; they say something which we can not understand, because we don’t know their language, that is all. But I’m sure they don’t make puns.”

In 1850, Millet completed and exhibited “Sower.” It was sent, along with “The Sheaf-binders” to the Salon. “Sower” would be copied and reproduced in lithography by others. Theophile Gautier was particularly impressed and wrote that of all of the peasants sent to the Salon that year, ‘The Sower’ was preferred.

In 1850, Millet completed and exhibited “Sower.” It was sent, along with “The Sheaf-binders” to the Salon. “Sower” would be copied and reproduced in lithography by others. Theophile Gautier was particularly impressed and wrote that of all of the peasants sent to the Salon that year, ‘The Sower’ was preferred.

It would truly appear that Millet was discovering himself and had found the type of paintings he was meant to paint.

In a letter to Sensier, we see Millet as he saw himself – a humble man who has begun creating his own definition and description of humanity as his work. Unfortunately, while Millet sought to show man’s humanity as he saw it; many believed his paintings were the work of a subversive socialist. His own words tell us that there was no ulterior motive to his choice of subject matter:

“But, to tell the truth, the peasant subjects suit my temperament best; for I must confess, even if you think me a socialist, that the human side of art is what touches me most, and if I could only do what I like, – or, at least, attempt it, – I should do nothing that was not an impression from nature, either in landscape or figures. The gay side never shows itself to me. I don’t know where it is. I have never seen it. The gayest thing I know is the calm, the silence, which is so sweet, either in the forest or in the cultivated land – whether the land be food for culture or not. You will admit that it is always very dreamy, and a sad dream, though often very delicious.

“You are sitting under a tree, enjoying all the comfort and quiet of which you are capable; you see come from a narrow path a poor creature loaded with fagots [a bundle of sticks used as firewood]. The unexpected and always surprising way in which this figure strikes you, instantly reminds you of the common and melancholy lot of humanity – weariness. It is always like the impression of La Fontaine’s ‘Wood-cutter,’ in the fable:

” ‘ What pleasure has he had since the day of his birth?

Who so poor as he in the whole wide earth?’

“Sometimes, in places where the land is sterile, you see figures hoeing and digging. From time to time one raises himself and straightens his back, as they call it, wiping his forehead with the back of his hand. ‘Thou shalt eat they bread in the sweat of they brow.’ Is this the gay jovial work some people would have us believe in? But, nevertheless, to me it is true humanity and great poetry!

“But, I stop, lest I should end by tiring you. Forgive me; I am all alone, with no one to whom I can speak of my impressions, and I let myself go without thinking. I will not do so again. Oh, now I think of it, send me from time to time some fine letters with the Minister’s seal, – a red seal and all the prettiness possible. If you could only see the respect with which the postman gives them to me, hat in hand (a thing quite out of the common), saying, with the greatest unctuousness, ‘From the Minister!’ It gives me a position, it increases my credit, for to them a letter with the Minister’s seal is, of course, from the Minister.”

Millet’s grandmother died early in 1851. The artist was devastated and heartbroken that he had not seen her in years. His mother wrote of her own great hardships – the other children left home for Paris and her physical ailments were a great burden. She worried how he was able to provide for his family and lived with the hope of one day seeing her beloved Francois again. Poverty would keep the two apart. She died in 1853, after waiting two years, in vain, to see her son again. Thinking of Tobit and his wife, who also waited, Millet began working on “Waiting”; a work in which two old people look toward the sky, and try to find a human form amid the glories of the setting sun.

Millet exhibited “Ruth and Boaz,” “The Sheep-shearer,” and “The Shepherd” in the Salaon of 1853. All were highly praised and Millet received a second-class medal. An American purchased “Ruth and Boaz” and William Morris Hunt purchased the other two paintings. Hunt, a student of Couture, was “seriously enamored” of Millet’s work and would study the man and the painter.

Hunt, an American, enjoyed a happy and care-free life in Barbizon. Hearn and Babcock (a student of Millet’s in 1848) came to visit Hunt. All three became disciples, of a sort, of Millet and purchased a number of his pieces. Millet finally, had found some relief from the poverty he had suffered for so many years. The funds unfortunately did not last long and Millet’s creditors were shortly knocking on his door threatening to withdraw his daily bread, other groceries and furniture.

Millet begged Sensier to find buyers for his work, at any price. Sensier was able to sell some, often at laughable prices, upon the guarantee that the buyer could get a refund if they later felt they had made a bad bargain. Quite often these paintings were returned which left Sensier scrambling to repay the purchase prices. Through these unusual circumstances, he would acquire many of Millet’s paintings. Despite the financial hardships this placed on Sensier, he continued to support Millet and his work; convinced Millet was a great painter.

Rousseau found a new buyer for Millet. M. Letrone, who was so enthralled with Millet’s work that he purchased a painting of a woman feeding chickens for the enormous price of 2,000 francs. Millet used the money to finance a trip home. Most of those he had known were gone. Yet, their memories inspired him. He drew everything which the family had owned – the house, the garden, the cider-mill, the stables, the orchard, the hedges, the pastures and the covered ways of the ancestral house. These drawings would serve as inspiration for a number of later works.

In 1857, Millet submitted “The Gleaners” to the Salon; shown here on the right. The art world could not dispute the talents of the painter though they tried. Some saw the three women as “savage beasts threatening the social order” and a plea against the misery of the people. Some saw him as a vanquished partisan and his work that of a socialist.

In 1857, Millet submitted “The Gleaners” to the Salon; shown here on the right. The art world could not dispute the talents of the painter though they tried. Some saw the three women as “savage beasts threatening the social order” and a plea against the misery of the people. Some saw him as a vanquished partisan and his work that of a socialist.

Sensier admits that thoughts of suicide did plague Millet. The artist was not always paid for his work. He was often ill, anxious and in fear of his creditors. He even created several tragic sketches of suicides. Sensier mentions one of a painter lying dead at the foot of his easel and the sorrow of the woman who finds him. His faith and inner strength led Sensier to believe that while the artist pondered the act, he would have never actually acted upon those thoughts. Millet drew his inner strength from the peasants he would paint, something as simple and beautiful as a sunset or walking among the trees he saw as friends.

In 1859, Millet finished what would perhaps become his most famous work, “The Angelus.” It depicts a couple, after a day of toiling in the potato field taking a moment to answer the call to evening prayers. While Sensier and other biographers do not say so, some believe the work was commissioned and declined by the buyer.

In 1859, Millet finished what would perhaps become his most famous work, “The Angelus.” It depicts a couple, after a day of toiling in the potato field taking a moment to answer the call to evening prayers. While Sensier and other biographers do not say so, some believe the work was commissioned and declined by the buyer.

That same year, four of his pictures were put up for auction by their original purchaser. The prices realized discouraged Millet and left him concerned if his current work would keep his wife from being confined (imprisoned) for non-payment of their bills. His troubles increased when that year’s submission to the Salon, “Death and the Wood-cutter” was declined.

It another turn of irony, the jury’s refusal of that work created a stir. Millet claimed it proved there were those who were determined to hurt his ability to make a living from his art. Paul Mantz and Edmond Hedouin published a piece in the “Gazette des Beaux Arts” expressing their indignation at the decision. Alexander Dumas was one of those who protested his exclusion, “The subjects, you say, are melancholy. Who knows if the artist does not tell a story with his brush, as we with our pens? Who knows if the artist does not write the memoirs of his own soul, and that he is not in despair himself at seeing these poor men work without any hope of calm, of repose, or of happiness?”

The incident, along with his continuing money woes led to another brush with death for Millet. He was so ill, that he was spitting blood and very near death.

Just when Millet needed some support, it came in the form of an un-announced and secretive visit by Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps (1803 – 1860). He told Millet, “Your pictures please me very much. You go to work with freshness and without fatigue.” and asked to see some of his work. He admitted to Millet that he didn’t want to see any other artists so he had left his horse at the edge of the village and gone through the gardens to avoid meeting anyone else. He would covertly visit with Millet several times before his death.

In the spring of 1860, life would change dramatically for Millet. He entered into a three year contract which permitted him to paint and draw whatever he wanted but all of his work would be given to only his new patron. The patron paid Millet 1,000 francs a month for the privilege. Millet, noted Sensier, was happy; as if an old dream was finally coming true.

The Salon of 1861 included three Millet paintings – “A Woman Feeding her Children”, “Waiting” and “The Sheep-Shearer.” Other artists were quite enthusiastic and complementary of Millet’s submissions. The critics were hostile. The public appeared to prefer the submissions of Jean-Leon Gerome (1824-1904) and Gustave Courbet’s (1819-1877) landscapes. “Waiting” was singled out for ridicule with derogatory caricatures and jokes. Not all of the critics took part in the criticism and Theodore Pelloquet was quite supportive of “The Sheep-Shearer.”

1862 was both a productive and unsettling year for Millet. One of Millet’s children had been seriously ill. With the arrival of the new year, the child returned to health. Millet painted a series of paintings which Sensier said were “wholesome, robust offspring of Millet’s genius.” He wrote of a number of headache events and an unexplained fever.

But, perhaps the most significant event would be the death of Vallardi in November. Millet was among the first on the scene of what was deemed a suicide. (I question that it was a suicide since the man died of 17 stab wounds to his torso and his bloody handprints were found on the walls, curtains and bedding upon which he was found.) Sensier shares some of Millet’s letters regarding the suicide but implies he has respected the artist’s personal feelings and has not included all the heartache Millet shared in his letters regarding the suicide.

Once again, the Salon would greet Millet’s submissions unfavorably. “A Peasant Leaning on his Hoe,” “A Woman Carding Wool,” and “A Shepherd Bringing Home his Sheep” were submitted in 1863. Millet remained home, while the members of the jury engaged in great debate, particularly over “A Peasant Leaning on his Hoe” which they felt indicated Millet was a Saint-Simonist.” [Saint-Simonism was a socialistic ideal where technology was somewhat ignored and man lived only by what he could produce through useful work.]

Millet submitted two canvases to the Salon of 1864. One, the “Shepherdess” would become one of his most famous works and was almost immediately described as a masterpiece. The other, drawn from his own personal experiences, depicted a sick calf being carried on a litter as if they were carrying a holy icon. The litter bearers were members of Millets own family. The press showed their chagrin at such posh treatment of a mere animal with great derision. Millet, in a letter to his friend Sensier, asks how were men meant to carry a calf but with the weight dispersed as it would be with a litter.

He would receive several offers for the Shepherdess and receive a medal for the work.

During this time, Millet would work on a number of architectural, decorative pieces. In 1865, he began a series of drawings for Emile Gavet. He worked with crayon, pastel and water-colors. When the collection was exhibited in 1875, many were surprised at the variety and grandeur of his work.

Millet submitted the landscape “Winter” and “The Goose-girl” to the annual Salon exposition in 1867. That was the same year of The Universal Exhibition of 1867. Artists could exhibit any of their works completed after 1855. Millet’s friends, with some difficulty, were able to gather the “Wood-cutter” which had been refused by the Salon in 1859; “The Gleaners,” “The Shepherdess with her Flock,” the “Sheep-shearer,” “The Shepherd,” “The Sheep-fold,” “The Potato-planters,” “The Potato-harvest” and “The Angelus”.

Around the time of Rousseau’s death, Millet’s debilitating headaches returned. He had a new client, Frederic Hartmann, but would die before he could complete the contract. Although he had no submissions in the 1868 Salon, he was remembered and honored. After 17 years of seemingly futile attempts to get the recognition his work deserved, he was made Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. When the award was announced, the crowd erupted into applause, something the Administrators of the Salon did not expect and might have been troubled by. After all, Millet was only a “rustic painter.”

The rustic painter, did at times, appear unsophisticated to those around him. He endeavored to create a book called “Sonnets and Etchings.” Intending to limit the publication to 350 copies, the plate etchings for the illustrations were set to be destroyed. Millet fought against having the works of art destroyed. It took some convincing to make him understand that destruction of the plates proved to purchasers that no more proofs could be printed. He wrote of his decision in 1869, “I have consented to the destruction of my plate, in spite of my desire to keep it. Between ourselves, I consider this destruction of plates the most brutal and barbarous of proceedings. I am not strong enough on commercial questions to understand the use of it, but I know that if Rembrandt and Ostade had each made one of these plates, they would have been annihilated.”

It was perhaps the Salon of 1870 that truly marked a change in attitude towards Millet and his work. During jury selection for that year’s Exposition, he was the sixth artist, of 18, to be elected. He exhibited a landscape entitled “November” and “Woman Churning” that year.

Unfortunately, Paris in 1870 was not the best place for an artist. During the Siege of Paris by the Prussians, Millet writes of his fears of being seen drawing and that he would be strangled or shot by Parisians, who might think he was a Prussian. He was arrested and appeared before a military bureau but was not included in the public reports. He was “ordered not even to pretend to be holding a pencil.” He also wrote of the personal frustration of not being able to sketch the country or the sea and being detained numerous times despite not even carrying a notebook and pencil in public.

I did a quick bit of research. It did seem that carrier pigeons and hot air balloons were used to secret messages into and out of Paris during the Siege. Some photographers and printers participated in the dissemination of these messages. It goes beyond the scope of The Famous Artists to pursue this further but it might make for an interesting bit of research for someone as to how the artists of France might have been aiding the French army during the Siege.

As 1871 came to a close, Millet and Sensier traveled throughout France. Millet, would visit his former home and walk the fields he and his family once tended. Now, they were in the hands of strangers and Millet was much distressed over how the faces he once knew so well were all gone.

By 1872, Millet had returned to Barbizon. Financially, he was somewhat secure; perhaps, for the first time in his life. He had more requests for paintings than he could fulfill and his pictures were getting increasingly higher prices. The critics may still have questioned his choice of subjects but there was little they could dispute in his talent. Unfortunately, after the horrors of occupied France and the death of his dear friend Rousseau, Millet’s health declined. He was able to spend fewer hours of the day painting.

Millet had been a somewhat prolific writer of letters. But, in the early spring of 1873, his declining health appears to have led to a virtual stop of written communication. In 1874, Millet was commissioned to paint the “Miracle des Ardents” and the procession of the shrine of Sainte Genevieve in all eight subjects, four big and four little. He immediately began to make charcoal sketches. He would not live to complete the work.

Despite his increasingly weak state, Millet continued to paint throughout the fall of 1874. By December, he was often feverish and suffered spates of delirium and complete exhaustion. He spent his more lucid moments with his family, begging them to keep together once he was gone. As the year came to a close, Millet took to his bed; never to rise again. On the 20th of January, 1875, he breathed his last.

On the 6th of April, an exhibition and sale of his works was held to benefit his family. The contents of his studio were sold and the collection was sold in June.

Millet’s work would inspire other famous artists. Vincent van Gogh called him “counselor and mentor in everything for young artists.” Claude Monet’s landscapes would be influenced by Millet’s representations of the coast of Normandy. Georges Seurat would also be influenced by Milet’s work.

A quiet painting of two sewing women by the French artist Jean-Francois Millet.

Early work by Jean Francois Millet. The Sower features a young peasant sewing seeds which critics claim was a political piece about the plight of the poor.

One of Jean-Francois Millet’s most famous works, The Angelus is about hard work and an abiding faith.