Shibata Zeshin (柴田是真) was a Japanese artist who is most well-known for his innovative use of lacquer. He was born in 1808 in the city of Edo, present-day Tokyo. At the time, the Japanese had not yet adopted the Gregorian calendar and one biographer listed Zeshin's date of birth as February 31st. Both his father and grandfather, Izumi Chobei, were shrine carpenters and wood carvers. His father had assumed his wife's family name of Shibata and was an Ukiyo-e painter, who had studied under Katsukawa Shunshō.

By the age of 11, young Zeshin was on his way to becoming an artist. He began his study of art with an apprenticeship to the well-known local lacquer artist Koma(n) Kansai. At 13, Zeshin dropped his own name, Kametaro, and called himself Junzo. His first teacher, perhaps realizing the talent in Zeshin, sent his student to study under Suzuki Nanrei to learn how to sketch, paint and create original designs. Adopting portions of his teacher's names, Junzo was dropped and Zeshin began signing his works “Reisai”, the same name he would later give to his son.

While studying with Nanrei, this “true artist” was given the name Zeshin, a reference to an Old Chinese tale of a king who held an audience with a great number of painters. In the story, the painters afforded the king the respect his position deserved. One artist reported before the king half-naked and without bowing to the king, sat down and commenced licking his paintbrush. The king, most likely to the great shock of everyone present, exclaimed “now, this is a true artist!”

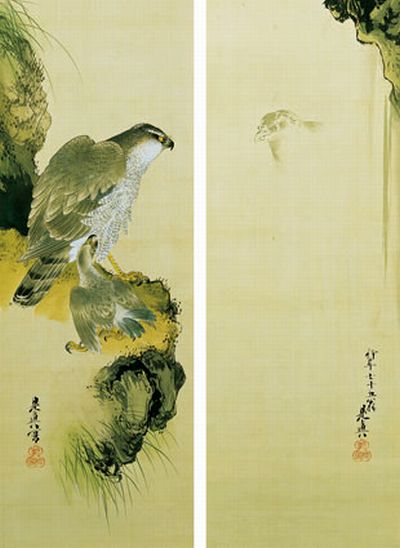

In 1830, Nanrei sent his student to his own teacher, Toyohiko Okamoto in Kyōto. He spent two years studying under Okamoto and it was during that period that he met Rai Sanyo. Sanyo was the author of a well-known book on Japanese history. Perhaps influenced by that meeting, Zeshin studied the Japanese tea ceremony, waka poetry, haiku, history, philosophy and literature. In later years his seemingly simple but well-thought out paintings would be compared to the simple and compact beauty of the haiku.

Under Okamoto's tutelage, Zeshin completed a number of fan paintings. Okamoto introduced Zeshin to many eminent artists who granted him access to many old treasures residing in a number of Kyōto's famous temples. He copied the famous works to further develop his skills and began making a name for himself as a painter.

In 1835, Zeshin inherited the Komo School workshop upon the death of his teacher Kansai and began taking in his own students. He is remembered as being a great teacher who only took in the best students including such well-known artists as Koami-ise, Inomote Chikugo, Nara Tosa and Matsuno Oshiu.

The 1830s were a period of great turmoil in Japan. Many areas were suffering from famine, epidemic disease outbreaks, riots, peasant uprisings, and religious pilgrimages all of which illustrated the need for change in Japan.

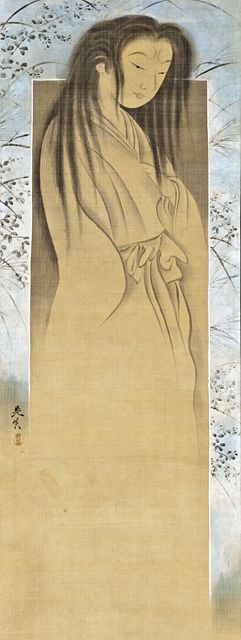

In 1839, he was commissioned to paint Ibaraki for a panel to be placed in a Shinto Shrine. The Famous Artists has included the left-side of this painting, Ikbaraki. 10th century Japanese folklore tells the story of a female demon, Ibaraki, who haunted Kyōto's Rashōmon gate and the courageous young samurai named Watanabe no Tsuna who was sent to slay the demon. Ibaraki was harrassing people and animals traveling through the gate and Watanabe's superior sent him to deal with the demon. When Watanabe approached the gate, the demon attacked him from behind and the samurai survived by cutting off the demon's forearm. The loyal retainer, presented the severed arm to his superior, Minamoto no Raiko. Raiko placed the arm in a locked chest. The demon, in the guise of his aunt, asked Raiko to see the arm. When he opened the chest, the demon showed her true form, snatching her arm and disappearing. Zeshin had his young student Ikeda Taishin wear a kimono and pose for the painting while holding a large daikon radish to represent the severed arm.

Zeshin's painting is considered by some to be something of an allegory of the merchant class's desire to end the reign of the shoguns.

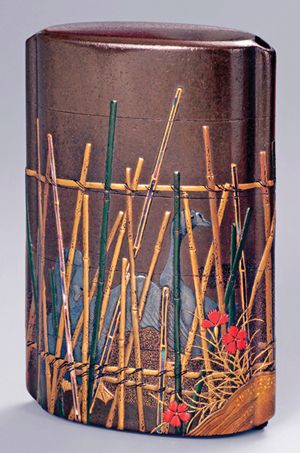

While the turmoil in Japan had little impact on Zeshin's personal life, it did begin to impact his art. Laws now limited the use of silver and gold for artistic use. Up to this time, most lacquered items were decorated with precious metals, ivory, coral and shell. These laws against conspicuous consumption led to a number of innovations in the use of lacquer by Zeshin. Zeshin added cereal starch, charcoal, bronze dust, vinegar and iron oxide filings to create a number of new techniques while continuing to honor the traditional styles. History has preserved many of his innovative techniques, but some unfortunately died with the artist.

In 1854, the United States Navy forced the opening of Japan to the outside world with the Convention of Kanagawa. Additional treaties with foreign governments opened up the country even further. In 1855, a major earthquake (the Ansei Eathquake of 1855) destroyed much of Edo, the bakufu capital. The government offices were severely damaged. In Japanese culture, giant catfish symbolized earthquakes. Consequently, much of the art during this period included catfish images.

Civil unrest and worsening conditions led to the Boshin War, a civil war from 1868-1869 between the ruling Tokugawa shogunate and those seeking to return political power to the Imperial Court.

The new government, wanting to expand Japan's influence and grow trade, hoped to use art as a way to introduce their culture to the rest of the world. In 1869, Zeshin was given a major role in the new government. His Imperial Majesty, the Emperor of Japan, honored Zeshin by commanding him to paint several pictures that would be included in the Austrian Exhibition. In 1873, he painted a number of pictures on silk, also through a commission of the young government. In 1876, Zeshin was given the position of public examiner of fine art and became a member of the Oriental Art Society. He was Japan's official representative at a number of international exhibitions. In 1890, Zeshin was granted membership in the newly-created Imperial Art Committee. Only 53 artists were honored as Imperial Commissioned Artists between 1890 and 1944.

Zeshin lived in interesting times. While his country and other Japanese artists were opening up to Western influence, he remained true to his traditional roots both personally and artistically. He was considered modern for his innovative techniques in the use of lacquer but also old-fashioned for his style. He held fast to many of the values his mother taught him as a child. She used to tell him that as art is the expression of thought, so the artists should be pure-hearted and noble-minded; and to run after fashion is unworthy of an artist. He famously refused a commission simply because it was to be displayed with work by a contemporary artist who did not meet his standards of morality and who had been imprisoned for drawing indecent pictures.

Shibata Zeshin invented techniques for creating lacquered pictures on paper that were flexible and able to be rolled for transport. His work, unlike the oils being used by so many of his contemporaries, never need re-touching and never fade. Sei Kai Nuri (blue sea lacquer) and Sei dō Nuri (Bronze lacquer) were among his inventions. It's believed he used a scratching tool made with a rat's tooth to imitate the grain of Chinese rosewood. Many in the art world identify Zeshin as the greatest Japanese lacquer artist who ever lived.

He married in 1849 and had a son, Raisai, but his wife and mother died shortly after the child's birth. Zeshin lived simply in a small house originally owned by his parents. When Zeshin died in 1891, one account claimed he left “little more than the materials for the work he had in hand.”